Public Domain Movies With Bela Lugosi

Whether one views him as an iconic master of the macabre or a troubled performer who never got the attention he deserved, Bela Lugosi’s name still rings bells — typically large ones, perched atop the spire of a weathered Gothic castle.

Bela Lugosi: Enduring Screen Icon

Born Béla Ferenc Dezső Blaskó in 1882 to a middle-class family in Lugos, Austria-Hungary, Lugosi dropped out of school at age twelve to pursue his dream of becoming a thespian. For the next two decades, Lugosi traveled throughout the continent and beyond, acting in stage productions and early silent films before eventually ending up in America, where he landed a career-making role in the 1927 Broadway production of Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Though the quality of Lugosi’s artistic output waxed and waned in the thirty years that followed, his on-screen image remained largely tethered to the aesthetics of Count Dracula. Nevertheless, Lugosi boasts a diverse filmography peppered with pictures ranging from the seminal to the silly, the ground-breaking to the groan-inducing — all running parallel to the evolution of the horror genre at large.

Any retrospective of Lugosi’s oeuvre must begin with Dracula (1931), Tod Browning’s revolutionary touchstone, which saw Lugosi reshaping the vampire mythos with his languid, thoughtful take on the famed character. Rather than playing Dracula like a monstrous ghoul, as in F.W. Murnau’s unofficial silent adaptation, Nosferatu, Lugosi put his syrupy Hungarian baritone and twinkling gaze to good use, delivering a version of Dracula who might believably seduce his female victims. The film was massive commercial success, and still remains one of the most influential works of classic horror. This powerhouse launched the Universal Monsters franchise, soon spawning an even greater hit with the following year’s Frankenstein, and, in doing so, bringing to prominence the man who would become Lugosi’s greatest rival: Boris Karloff.

Lugosi’s next major role was in Victor Halperin’s White Zombie (1932) — a seminal picture which inspired filmmakers such as George Romero and Lucio Fulci to create their own visions of the undead. In it, Lugosi plays Murder Legendre, the owner of a Haitian sugar mill that employs brainless zombies for hard labor. The film is a stylistic delight, harkening back to the expressionism of the silent era, while allowing Lugosi free rein to exude hypnotic intensity. Still, although Lugosi’s star was still on the rise, Karloff’s was ascending into the stratosphere, resulting in a quasi-amiable “cold war” between the two thespians which spanned the 1930s and beyond. This offscreen tension informed one of Lugosi’s finest works of the era, Edgar G. Ulmer’s The Black Cat (1934), which saw him playing a widowed war veteran arriving at the Art Deco manor house of his nemesis, a twisted architect (Karloff) who kidnapped his wife and young daughter. Loosely based upon the Edgar Allan Poe short story of the same name, the movie is defined its awe-inspiring art direction, presciently fluid camerawork, and the go-for-broke competition between Lugosi and Karloff, as each attempts to act the other clear off screen. The duo rekindled this spark, albeit to a lesser degree, for The Raven (1935), in which Lugosi plays a Poe-obsessed surgeon with a makeshift torture chamber who takes advantage of Karloff’s witless escaped convict. Despite having twice as much screen-time as Karloff, Lugosi received only half of his co-star’s salary. Nevertheless, Lugosi next returned the well for Tod Browning’s Mark Of The Vampire (1935), a lesser-known but intriguing riff on vampire lore, which opts for a head-spinning twist ending that disappointed some viewers while shocking others. As the ’30s drew to a close, Lugosi again saw himself taking on Karloff in the latter’s final Frankenstein title, The Son of Frankenstein (1939). Despite accepting second billing, Lugosi steals the show as Ygor, a malevolent, broke-necked grave robber — physically transforming with a matted beard and a row of razor-sharp teeth. The film proved so successful that it commercially reinvigorated the Universal Monsters franchise, which had grown stagnant in the preceding years.

Unfortunately, due to a combination of poor financial management and chronic pain due to injuries he had received during earlier military service, Lugosi’s career began a slow backslide during the 1940s. Relegated to the “B-Film” assembly line, Lugosi churned out a number of derivative productions, such as The Return of the Vampire (1943), which transported a thinly veiled version of Dracula (here renamed Armand Tesla) into World-War-II-era London, where he teams up with a werewolf friend to embark on a reign of terror. The Corpse Vanishes (1942) is another entertainingly ludicrous bit of schlock, which sees Lugosi playing a mad scientist who injects his wife with blood drawn from virginal young women, aided by a pugnacious dwarf accomplice. The same could be said of The Ape Man (1943), in which Lugosi hams it up as another insane doctor who injects himself with primate blood before transforming into the titular creature — sporting a well-worn ape costume that seemingly found its way into half of the horror cheapies of the era. Lugosi also returned into the Universal fold in a diminished capacity, first returning as Ygor in the decent, if slight, Ghost of Frankenstein (1942), then playing a clunky version of the Frankenstein’s creation himself in the zanily fun monster mash Frankenstein Meets The Wolf Man (1943). He then finished out the decade with a return to Dracula’s cape for Abbot & Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948), which finds the classic comedy duo encountering the full rogue’s gallery of Universal creatures in a funny, yet surprisingly frightening genre-bender.

Sadly, Lugosi’s chronic pain had led him down a dark path of morphine addiction, which sapped him both mentally and physically. By the early ’50s, it seemed as though Lugosi’s career was over, until a hyper-energetic upstart named Ed Wood reached out to the actor. Inspired as a young man by Lugosi’s performances, the eccentric Wood was horrified to find his idol living in near-poverty, and promptly offered him one thousand dollars to play the narrator in Glenn or Glenda (1953), a forward-thinking, semi-autobiographical melodrama about a transvestite struggling with his gender identity.[5] The movie was Wood’s directorial debut and boasted many of the hallmarks that came to define his style: stilted dialogue, oddball fantasy sequences, and a fever-dream narrative. Lugosi and Wood continued their curious collaborations with Bride of the Monster (1955), in which Lugosi plays a familiar mad scientist who uses atomic energy to create superhuman beings. Tragically, this would the last film Lugosi would ever see released, as he succumbed to the ravages of his addiction, passing away on August 15th, 1956.

Nevertheless, Lugosi was cinematic-ally summoned back from the dead for one last adventure via Wood’s cult-classic Plan 9 From Outer Space (1959). In order to give Lugosi one final credit, Wood crammed a combination of B-roll and previously shot test materials of the aged actor into an otherwise unrelated narrative involving extraterrestrial invaders raising up the human dead in an effort to save mankind from itself. The resulting film is borderline incoherent and packed with wild moments of unintentional comedy. Though its reception certainly did not live up to Wood’s sky-high expectations, Plan 9 has come to earn legendary status among film buffs as the “epitome of so-bad-it’s good cinema”, and, even now, is still screened to raucous midnight crowds worldwide. Indeed, despite the ups and downs of his career and the somewhat tragic nature of his personal life, Lugosi’s legacy remains eternal, much like the undead characters he who was so adept at playing. In part, his cerebral, serious-minded performances helped transform horror from a fringe curio to a mainstream money-maker, allowing for an American renaissance in the genre — the effects of which still resonate today.

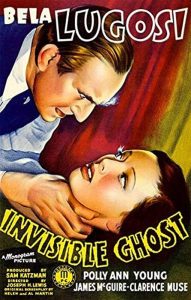

Bela Lugosi starred in a number of films that are now public domain movies. Among these are Plan 9 From Outer Space, Ape Man, Ghosts on the Loose, Vampire Over London, Invisible Ghost, Bowery at Midnight, Shadow over Chinatown, Spooks Run Wild, One Body Too Many, The Death Kiss, and Glen or Glenda? . The RetroFilm Vault specializes in serving the broadcast television and media community with broadcast quality public domain movie programming for classic films such as these. In addition, we have movie trailers for stock footage use of many Bela Lugosi movies.