Most Iconic Public Domain Films

What truly makes a film ‘iconic’? What makes us come back to films that are 50, 60, or even 100 years old? A truly iconic film is one that leaves a lasting impact on the culture after its release. Oftentimes these films are not recognized until years (or even decades) after their initial release. The following are the most iconic films in the public domain.

Night of the Living Dead

In 1968, George A. Romero made a big splash in the horror movie scene with his independently produced Zombie feature Night of the Living Dead. The film follows seven characters trapped within a farmhouse in Pennsylvania, unable to escape because of the Living Dead (Despite its significance in zombie movie canon, the word “Zombie” is never used in the film).

Produced on a budget of slightly over 100,000 dollars, Romero’s first feature film kick-started the Zombie subgenre of horror which continues to this day. It is notable not only for breaking taboos in onscreen gore and violence, but being the first feature film ever shot in Pittsburgh. Every piece of zombie media, from Zombieland to The Walking Dead owes a debt to Romero’s 1968 classic.

His Girl Friday

His Girl Friday is a classic example of one genre that isn’t too common nowadays – the screwball comedy. Featuring a young Cary Grant, and directed by Howard Hawks, this film follows the wacky antics of a newspaper editor as he prevents his co-worker (and ex-wife) from getting married. It is one of Quentin Tarantino’s favorite films.

In an interview with Peter Bogdanovich, Hawks mentioned that he always wanted to try overlapping dialogue – something that movies of the time just didn’t do. This required them to design a whole new sound system in order to record the actors’ incredibly speedy delivery. The estimated rate of dialogue in films at the time was 90 words a minute. The dialogue in His Girl Friday runs at 240 words a minute.

Not only did this production revolutionize sound recording, it re-defined the possibilities of comedic filmmaking as a whole.

The Brain That Wouldn’t Die

A classic mad scientist story, The Brain that Wouldn’t Die follows a man’s attempt to keep a head alive while detached from its own body. It was rejected in UK cinemas when submitted in 1961 – it didn’t receive a proper DVD certificate in that country until 2006. This film’s mix of corny B-Movie effects and some genuinely impressive camera trickery made it one of the first cult-classics of its kind.

Ever inspiring to its fans, this schlocky film has been repeatedly adapted into musical form for the stage, including in 2009, 2011, 2015, and 2016. It was also featured on the cult TV-Show Mystery Science Theater 3000 (Episode 512). A bonkers premise may have prevented it from a UK release in ’61, but that same premise made sure that over 50 years later, it still has an audience.

Reefer Madness

Originally entitled Tell Your Children, Reefer Madness follows an ensemble of teens as they discover marijuana and subsequently descend into insanity. Financed by a church group in an attempt to warn parents about teen marijuana use, it was widely ridiculed for its completely inaccurate depiction of marijuana.

Reefer Madness was rediscovered by B-movie fans in the 1970s, and is now a favorite among midnight movie fans for its ludicrous portrayal of drug addiction. This film essentially started the “so bad it’s good” subculture of movie fans, and remains one of the most popular attractions to that audience – many of whom enjoy the film while stoned.

D.O.A.

The epitome of Film Noir, D.O.A was released in 1950 directed by Rudolph Mate. It opens with one of the most iconic shots of classic noir – a long tracking sequence following a man through a police station to report his own murder. In its style and archetypal plot, D.O.A stands as the template for the film noir genre on screen – a genre where broad characterization and stylized lighting would not get in the way of labyrinthine plots and engrossing mysteries.

A famous scene in this film where Edmund O’Brien runs down Market Street in San Francisco was filmed without permits, and was shot without the knowledge (or permission) of city authorities. Because of this, you can see several stunned pedestrians in the final film as the panicking actor runs past them.

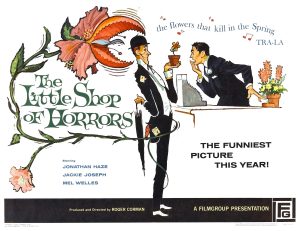

Little Shop of Horrors

Roger Corman has mentored countless acclaimed filmmakers, but never been a particularly acclaimed director himself. Ron Howard, Jonathan Demme, and James Cameron all got their start under Corman’s wing, but the man himself was content making B-Movies such as Little Shop of Horrors which became Corman’s most successful film due to its black humor and utterly unique premise.

Little Shop of Horrors has the unique distinction of being made on a whim – Roger Corman had made a bet that he could make a movie in two days, and this creature feature ended up taking two days and one night to film. This film was so influential it became a hit Off-Broadway musical in 1982, which was made into a feature film in 1986, before coming back to the stage for a 2003 Broadway revival.

It was also one of Jack Nicholson’s earliest performances – he plays a masochistic dentist patient in a one scene role.

Nosferatu

Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror was an unauthorized adaptation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula. In an attempt to skirt copyright laws, the titular character of Count Dracula was renamed Count Orlock, and the term “Vampire” was replaced with “Nosferatu”, now a term used to describe the character of Orlock himself. It ensured that Nosferatu would have its own identity outside of its cherished source material.

The appearance of Count Orlock, and striking use of shadows made Nosferatu an instant classic. From the shot of Orlock in the archway, to his shadow on the wall, the imagery of this film continues to ignite the imaginations of filmmakers to this day. Its aesthetic and atmosphere became part of the DNA of horror cinema.

A Trip to the Moon

A Trip to the Moon is the most well known work from French Filmmaker and inventor Georges Melies. Inspired by the science fiction novels of Jules Verne, this 18 minute short tells a brief fantastical tale of a group of astronomers who launch themselves to the moon from a cannon. Even if you have not seen this film, odds are you remember that striking shot of the Man in the Moon getting hit in the face with a rocket – fantastical images like that helped cement Melies’ work in cinematic history.

Despite being a revolutionary craftsman, Melies hit money troubles later in life and was forced to sell off the rights to his films. In 1923, Melies, in a fit of rage, burnt all his remaining negatives in his garden. For a period it was thought that all of Melies’ films were lost to time. However, journalists were able to find and restore A Trip to the Moon and many of his other films within his lifetime.

Birth of a Nation

Among the first narrative feature films, D.W. Griffith’s magnum opus Birth of a Nation enraptured audiences in 1915 with groundbreaking filmmaking techniques and a sweeping epic scope. It set a record for amount of extras, and became the first film to stage elaborate battle scenes with more than a handful of actors. The politics of the film aside, this was an awe inspiring piece to the audiences of the time, and it is often seen as the proper birth of American Cinema.

Besides being a watershed of American filmmaking, Birth of a Nation is also notorious for its positive portrayal of the Klu Klux Klan – it is often credited with the Klan’s revival that same year. The NAACP heavily protested the film’s premiere, and the film was banned from many larger cities (including Los Angeles and Chicago) upon its release. A year later, D.W. Griffith released the film Intolerance as an apology for the racial backlash to Birth of a Nation.

Metropolis

Fritz Lang’s Metropolis is the most important science fiction film ever made. Not only did it introduce the concept of androids into cinema, it was also a key influence on the aesthetics and themes of future classics such as Blade Runner and Star Wars (C-3PO’s design was directly inspired by Futura, the robot in this film). A wildly expensive film (if made today, it would cost over 200 million dollars), it nearly bankrupted its production company, UFA, during filming.

Despite its humanist message of solidarity between classes, this film was a particular favorite of Adolf Hitler’s. Because of this, he would later offer Lang a leading role in crafting Nazi Propoganda films in 1934. Lang, a vocal critic of the Nazi movement, refused and immediately fled the country. He continued to make films in America until his death in 1976.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari

Another German-produced masterpiece, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is a quintessential entry in the Expressionist movement. This film was essential in drawing international attention to German cinema. While it polarized audiences upon its release, it struck enough of a chord that one Paris theater continued to screen it for 7 years after it opened.

Perhaps most well known for its daring set design and stark lighting, this film also pioneered many narrative techniques that would not become popular in American Cinema for years, especially the heavy use of dream sequences, and ghoulish figures that would heavily influence the horror genre (a categorization that did not exist at the time of this film’s release). While many films had macabre elements before, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is widely known as “the first true horror film”.

Let’s All Go To The Lobby

First released in 1953, Let’s All go the the Lobby is a staple of American movie theaters all over the country, including in it an iconic jingle meant to play during intermissions. The company that created it has continued selling copies of the animation since its production, and independent movie theaters across the country still play it before modern films (even though intermissions are no longer a common practice in movie theaters). To this day, this tiny little animated film is integral to the theater experience.

Duck and Cover

Among the most famous relics of the Cold War is this quirky little mostly-animated film called Duck and Cover. Its aim was to teach kids how to properly brace for a Nuclear attack by ducking and covering as soon as they saw a flash in the distance. This comes off as laughable today, because the simple act of hiding in a crouched position is not going to protect one from a Nuclear blast or fallout. Nowadays, it is the most well known reminder that in 1951 we were oddly comfortable with the possibility of Armageddon.